Using a Bloom Filter to Anonymize Web Server Logs

Monday 17th December 2018

Since May 2018 when the GDPR came into full effect, I have had web server access logging completely disabled for my site. This is great from a security, privacy and GDPR compliance point of view, however it meant that I had very limited insight into the amount of traffic my site was getting.

In order to solve this problem, I have built an open-source log anonymization tool which will remove personal data from web server access logs, and output a clean version that can be used for statistical purposes. A Bloom filter is used to identify unique IP addresses, meaning that the anonymized log files can still be used for counting unique visitor IPs.

I've released the tool under the MIT license, and it's available on my GitLab profile: https://gitlab.com/

Skip to Section:

Using a Bloom Filter to Anonymize Web Server Logs ┣━━ Overview of the Tool ┣━━ What is a Bloom filter? ┣━━ Finding the Optimal Bloom Filter Configuration ┣━━ Fuzz Testing with Radamsa ┣━━ Implementing the Tool ┣━━ GDPR ┗━━ Conclusion

Overview of the Tool

The tool is written in Python 3, and is capable of anonymizing web server access logs produced by web servers such as Apache or nginx.

If you run the following log entry through the tool:

127.0.0.1 - - [16/Dec/2018:16:07:23 +0000] "GET /pages/page1.html?query=string&query2=string2 HTTP/1.1" 200 11576 "https://www.example.com/path/file.html?query=string&query2=string2#fragment1" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Ubuntu Chromium/71.0.3578.80 Chrome/71.0.3578.80 Safari/537.36"

...the anonymized output will be:

192.0.2.1 - - [16/Dec/2018:16:07:23 +0000] "GET /pages/page1.html HTTP/1.1" 200 11576 "https://www.example.com" "Chromium"

A Bloom filter is used to keep track of which IP addresses have been seen before. This is what allows the outputted log files to be used for counting unique visitor IPs. Other anonymization solutions rely on obfuscating, invalidating or removing IP addresses, which usually limits or prevents them being used for this purpose.

User agent strings are compared against approved lists of browsers and web crawlers, and replaced accordingly. The output log files will contain only the browser name, such as Chrome or Firefox, rather than the full user agent string including version numbers, etc.

Referrer URLs are stripped down to only the scheme (such as https) and Fully Qualified Domain Name (such as www.jamieweb.net).

The HTTP Basic Authentication user ID and the RFC1413 identity (Ident protocol) are completely discarded. These aren't used very widely anyway.

Please see the README for the tool in the GitLab repository for further details.

A screenshot of the GitLab repository page at https://gitlab.com/

The anonymized logs can be fed into a statistics tool such as AWStats. Of course an amount of accuracy and detail is lost during the anonymization process, however key information such as the number of unique visitors, page views and referring sites is still available. This is a fantastic balance between using an intrusive, JavaScript-heavy client-side tracking and having no insight at all.

What is a Bloom filter?

A Bloom filter is a data structure that can be used for determining whether a particular piece of data exists within a set, without actually requiring access to the set itself.

They consist of an array of bits, and can be either written to, or queried. If you want to add a piece of data to a Bloom filter, hashes of the data are generated, and the corresponding bits in the Bloom filter are set to 1. Full, cryptographically secure hashes are not normally used - instead, they are split into segments (such as 5 characters at a time), or other algorithms such as murmur are used.

For example, imagine a brand new Bloom filter which is 16 bits in size:

0000000000000000

If we want to add the data helloworld to the Bloom filter, we must first generate a hash of the data. The maximum potential value of the hash should be the same size as the Bloom filter. In this case, the Bloom filter is 16 bits in size, so the maximum value of the hash can be 16:

$ echo "helloworld" | sha256sum 8cd07f3a5ff98f2a78cfc366c13fb123eb8d29c1ca37c79df190425d5b9e424d -

The SHA-256 hash value of helloworld is obviously significantly larger than 16 when converted to base 10, so we need to cut it down to an appropriate size. SHA-256 hashes are represented in hexadecimal (base 16), meaning that each character can represent the values 0 to 15 in base 10.

This means that in this example, one single character could represent each of the bits in the Bloom filter uniquely, so we need to split the hash into one character segments. You can use as many segments as you wish, however generally only a few are used. In this case, we'll use two segments.

The more segments we use, the more accurate the Bloom filter will be, however the capacity of the filter will be reduced. Increased accuracy may sound like a good thing, however in many use cases (such as anonymizing web server logs), being too accurate can actually result in the Bloom filter being easy to brute-force, potentially revealing the original un-anonymized data.

The first two single-character segments of the hash are 8 and c. When converted to base 10, these equal 8 and 12 respectively.

This means that we need to set the 8th and 12th bits of the Bloom filter to 1. Since we're talking arrays, and arrays start at 0, that's really the 9th and 13th bits:

0000000010001000

^ ^

Now let's add another piece of data to the filter:

$ echo "123" | sha256sum 181210f8f9c779c26da1d9b2075bde0127302ee0e3fca38c9a83f5b1dd8e5d3b -

The first two segments in base 10 are 1 and 8. So we'll set the 2nd and 9th bits to 1:

0100000010001000 ^ ^

Notice how the 9th bit was already set. There is no problem there, it's already set so it can remain set.

Now we can query the Bloom filter to determine whether a particular piece of data exists:

$ echo "wheel" | sha256sum 1f148121b804b2d30f7b87856b0840eba32af90607328a5756802771f8dbff57 -

The first two segments in base 10 are 1 and 15, so we need to check whether the 2nd and 16th bits are both set to 1:

0100000010001000 ^ ^

As you can see, only one of required bits is set to 1, so this proves that the data is definitely not present in the Bloom filter.

Let's try querying the filter again:

$ echo "helloworld" | sha256sum 8cd07f3a5ff98f2a78cfc366c13fb123eb8d29c1ca37c79df190425d5b9e424d -

As we worked out previously, the first two segments in base 10 and 8 and 12, so we again need to check the 9th and 13th bits:

0100000010001000

^ ^

Both of the required bits are set, so this proves that the data might be present in the filter.

Bloom filters have a non-zero inaccuracy rate. Querying a filter will give you either one of two outputs: that the data might exist, or that the data definitely doesn't exist. In other words, false positives are possible, but false negatives are impossible. This doesn't make them useless though, as there are many use cases where 100% accuracy is not required.

The most well-known use of Bloom filters is performance and efficiency. Querying large databases or other sets of data directly can take a large amount of computer processing power and time, so having a Bloom filter for the data set and querying that first can help to narrow down the search, potentially resulting in huge performance increases for the system.

Finding the Optimal Bloom Filter Configuration

One of the first challenges that I faced when starting this project was in finding the most optimal Bloom filter configuration. I needed a Bloom filter that is accurate, but not too accurate, and can also store a large amount of entries.

However, the most important factor in this case is security, so above all I needed a Bloom filter that would be resistant to brute-force attacks should somebody gain unauthorized access to it.

The term 'brute-force attack' may sound unusual when talking about a Bloom filter, however in this particular case it is a very real threat. Since the filter will be storing IP addresses, the data is very predictable. There are only a total of 3,706,452,992 (3.7 billion) publicly routable IPv4 addresses available, which may sound like a large number, but in reality it would only take a few seconds for a computer to query the Bloom filter with each one of these. For IPv6, it would take much longer, but the risk is still there.

In order to eliminate this risk, the Bloom filter needs to be inaccurate enough that it's not possible to uniquely identify a single IP address. In other words, there needs to be a certain amount of k-anonymity for IP addresses stored in the filter. This is achieved by using a filter that is smaller than the total number of possible IP addresses, and using a total combined hash length that doesn't allow IP addresses to be uniquely identified.

As I discussed in the previous section, the size of the Bloom filter should be tied to the maximum possible value of a single input hash segment. This means that we need to find a segment length which provides an adequate level of inaccuracy when used with IPv4 addresses.

Let's try 6 characters, where the maximum potential value (ffffff) is 16,777,215 (16.7 million). Divide this number by the total number of publicly routable IPv4 addresses:

3706452992 / 16777215 = 220.921827133

This means that on average, each 6 character hash segment will represent ~221 unique publicly routable IPv4 addresses. In other words, if you were to brute-force the Bloom filter, there would be an average of 221 IP addresses that match every entry, which prevents you from accurately identifying a single unique one.

It's up to you whether ~221-anonymity is an acceptable amount, however for my system I decided to go with 5 character hash segments. The maximum potential value (fffff) is 1,048,575, so let's divide this by the total number of publicly routable IPv4 addresses:

3706452992 / 1048575 = 3534.75239444

This results in ~3535-anonymity, which I believe is a much more acceptable value for my particular setup.

For this sort of use, it's best to only use a single hash segment with the Bloom filter. Using multiple would effectively increase the length of the hash used to identify unique IP addresses, causing the k-anonymity value to be either significantly reduced or completely eliminated.

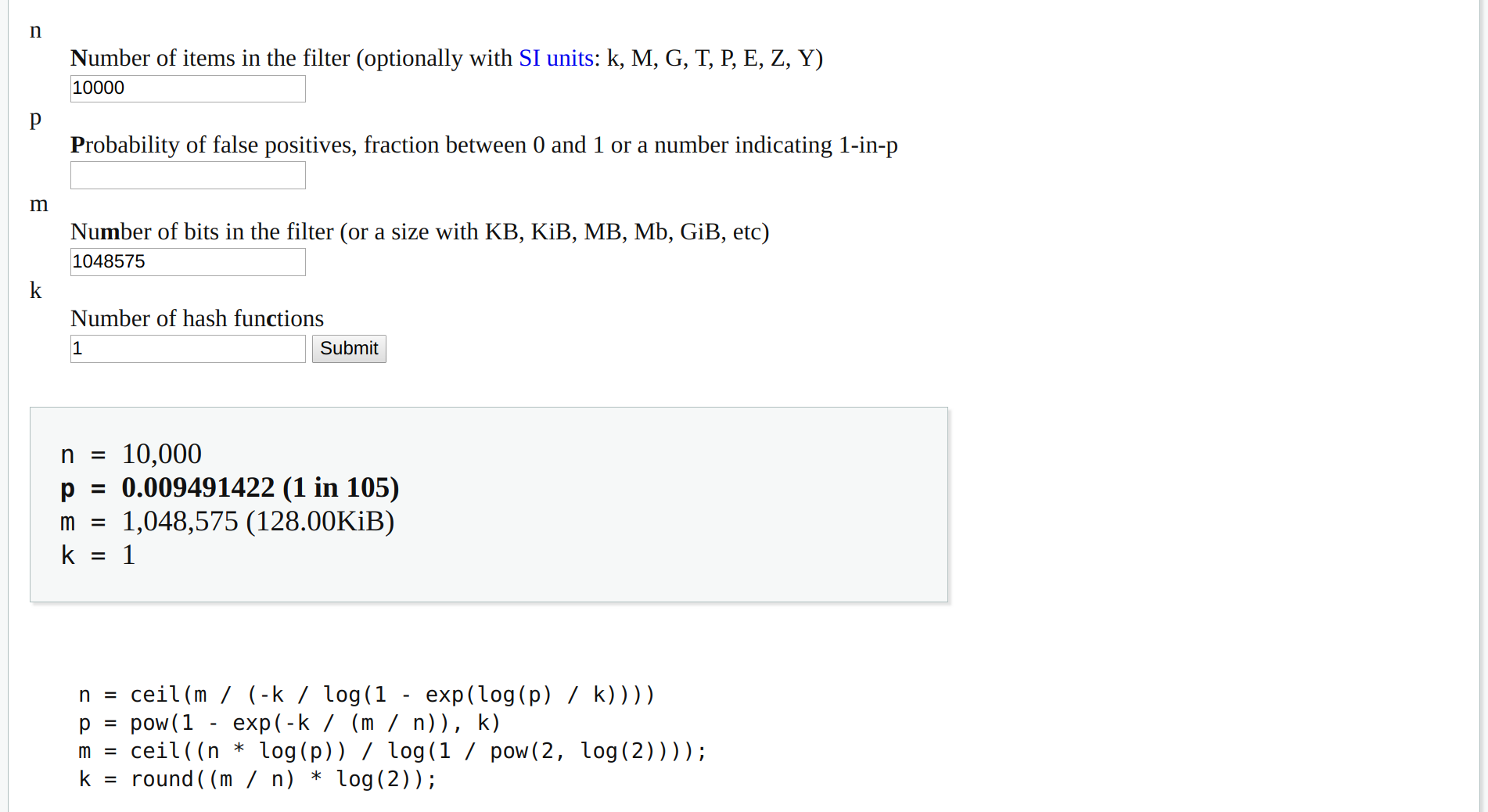

Based on these calculations, the Bloom filter configuration that I decided to go with for my own system is:

- Size: 1,048,575 bits (128 KiB)

- Hash Segment Length: 5 characters (1,048,575 possible unique values)

- Hash Segment Count: 1

These values can be easily controlled in the configuration file for the tool.

I also recommend having a look at the Bloom Filter Calculator on hur.st, as this is an extremely useful tool for testing different configurations and seeing the properties that they have.

A screenshot of the Bloom Filter Calculator at https://hur.st/bloomfilter/.

Fuzz Testing with Radamsa

I've written a basic fuzzing test harness for the tool in order to assist with identifying any potential vulnerabilities. My fuzzing engine of choice is Radamsa, however you should be able to swap in a different tool if you prefer.

You'll probably have to adjust the file paths to get this working on your system, but other than that it should work as-is. You must provide some sample log entries to be fuzzed in rawlogs/radamsa-sample.log, or whichever path you choose:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Please ensure that you run this fuzzing script on a tmpfs/ramdisk, as the high-speed and repeated writes may damage your hard disk or SSD."

while true; do

radamsa rawlogs/radamsa-sample.log > rawlogs/raw-access.log-input

output=$(python3 /home/bloomfilter/bloomfilter/web-server-log-anonymizer.py 2>&1)

if [[ $(echo "$output" | tail -n 1) != "Saving..." ]]; then

#Write crash log to file:

printf "**Found crash at `date`.**\n\nError output:\n" >> fuzz-output.log

echo "$output" >> fuzz-output.log

printf "\nFuzzed input:\n" >> fuzz-output.log

cat rawlogs/raw-access.log-input >> fuzz-output.log

printf "\n\n" >> rawlogs/fuzz-output.log >> fuzz-output.log

#Write summary to stdout:

printf "**Found crash at `date`. Last 10 lines of output:**\n\n"

echo "$output" | tail -n 10

printf "\n\n"

fi

rm outputlogs/access.log

done

Please ensure that you run this fuzzing script on a tmpfs/ramdisk, as the high-speed and repeated writes may damage your hard disk or SSD. The below command will create a 128 MB tmpfs for you to use:

sudo mount -t tmpfs -o size=128m tmpfs /path/to/desired/mount/directory

Then make sure that all of the files the script needs to read and write are on the tmpfs.

I've run this fuzzing script for around 12 hours so far. It found a couple of crashes within 10 minutes, which I've now fixed, but other than that nothing has been found. Please feel free to perform more of your own testing and let me know if you find anything.

Implementing the Tool

I've implemented the tool on a dedicated Raspberry Pi Zero W logging device. Every hour, the logs are transferred from my main web server to the Raspberry Pi using SFTP, where they are then anonymized.

The un-anonymized logs are removed from disk on the server just a few minutes after they are transferred to the Pi, and on the Pi itself they are erased as soon as they have been processed.

Finally, the anonymized data is fed into AWStats in order to give me a high-level statistical insight into the traffic on my site.

All of this is set up with cronjobs and a restricted service account for SFTP.

Please see the 'Use on a Live Web Server' section of the README for further details.

GDPR

Please note that I am not a lawyer and this is not legal advice. This is only my understanding and interpretation of the GDPR, and it may be inaccurate or incomplete.

While it's true that Recital 49 of the GDPR allows for the processing of personal data (such as log files) in order to ensure sufficient levels of network and data security, this particular clause does not expand to statistical and analytical purposes.

Article 5(1)(b) allows personal data to be (trimmed excerpt, see full legal text):

...collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes; further processing for (...) statistical purposes shall, in accordance with Article 89(1), not be considered to be incompatible with the initial purposes...

Article 5(1)(e) states that personal data must be (trimmed excerpt, see full legal text):

...kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary...

Finally, Article 89(1) states (trimmed excerpt, see full legal text):

Processing for (...) statistical purposes, shall be subject to appropriate safeguards (...) Those measures may include pseudonymisation...

As part of this project I have added a privacy notice to my site, which states which personal data is collected and how it is processed.

Conclusion

Overall I am very happy with the outcome of this project, and I believe that I've struck a good balance between more traditional 'tracking' methods, and having no statistical insight at all.

I definitely don't believe that what I am doing is anywhere near what would traditionally be called 'tracking', and it's not even 'analytics' really as detailed usage patterns cannot be easily identified in the anonymized data. The new statistics which I have access to will allow me to assess the performance of my content and hopefully help with growing the site accordingly.